![]()

Robert Lavack ~ "Nun of That"

![]()

|

|

|

Nun of That |

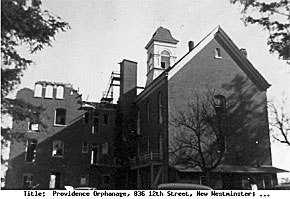

By Robert Francis When my father was training as a pilot in the Royal Air Force during WWII he had a Canadian classmate who refused to attend church services that followed the weekly church parades. RAF regulations stipulated that attending church parades was compulsory unless one was ill, or had a legitimate reason for not attending. But, attending the church service was not compulsory. There was a Damocles aspect to that waiver. Those who chose not to attend the church service were required to stand guard outside the church until the service was over. My father asked his friend why he didn’t compromise and take a book to read during the church service instead of standing outside in what was often inclement weather. He told my father that he had sworn an oath with orphan friends at an early age never to attend a church service if he had a choice. This oath was made when he was a ward of the Sisters of Providence who administered the Providence Orphanage in New Westminster, British Columbia. The cruelty of some Sisters in that institution had so embittered their young wards that his close-knit group swore a joint oath to reject any beliefs deemed sacred by the Nuns, and never to attend church if they had a choice. Being a practicing Christian, my father was naturally interested in what form of childhood experience could have made anyone so adamant. This is the story his friend related to my father.

I soon learned what it would be like to be a quasi-orphan in care of the Sisters of Providence. My uncle, an ordained priest of the Church, had arranged for our temporary stay at the orphanage as part of a trial separation agreement. He had counseled our parents to accept this before proceeding with their proposed divorce. Like the church hierarchy in those days, he viewed divorce as an excommunication sin and personally saw it as an embarrassment to our Catholic family. He had made this temporary arrangement to free our parents from childcare problems in the hope this might lead to a reconciliation. That was not to be. Unforeseen custody problems extended the three months to three years. To counter these bitter experiences, my friends and I formed a support group to minimize the ordeals imposed on us primarily by our dormitory nuns. Thinking about that period of my life, I am constantly amazed that orphans of five to eight years of age could survive in such a hostile environment. They did by developing projects and invoking fantasies to make their existence bearable. These pursuits ranged from creating their own form of currency based on the discarded nails from the high fence that had been built around the boys’ and girls’ segregated playing areas. Salvaging the nails was done by trolling small horseshoe magnets attached to lengths of string through the loose sand under the recreation fences. The magnets came from Christmas fishing game presents that used these to catch metal fish over draped sheets. Thesalvaged nails caught were straightened and given a coin value dependent on their size. These became a trading currency for items the orphans wished to buy or sell. Our orphan mentality was no doubt similar to that of criminals in a prison setting created to achieve fantasy situations. Those fantasies favoured by the orphans related to possible adoption. Being a quasi-orphan I could understand this longing and did my best to play my part in the fantasies. The favoured one portrayed the orphanage building as a monster poised on the brow of the hill overlooking New Westminster waiting to capture unsuspecting children for the black clad Sisters of Providence. We would then take turns in exercising our imaginations by relating how we escaped the monster’s clutches and found a joyous family life by recounting our celebrations with our adopting family after escaping. The segregated dormitories and recreation rooms in the ground floor of the building were designed to accommodate several hundred orphans ranging from five to 16-years-of-age. These extended back from the highway to form the legs of the ‘U’ structure. It was a sturdy and functional complex that could have been modified to serve as a maximum-security prison. Once in, it was difficult to get out. The boys and girls only came into contact as groups during daily morning mass, school classes and when participants in ‘bed wetter’ parades.

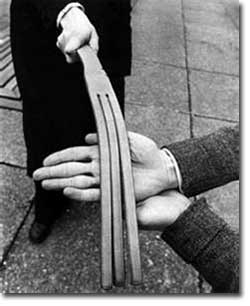

Draped in their soiled sheets the girls continued their crocodile parade towards the boys’ large recreation room and the boys towards the girls’. Once there they were directed to circle in the centre of these large rooms to be viewed as objects of shame by the spectator orphans of the opposite sex. The supervising Nuns waited until the crocodiles were established in a circulating pattern in the centre of the room before using their hand-held, castanet-like ‘clackers’ to initiate the degradation process. When all was to their satisfaction, the ‘clackers’ were sounded with increasing tempo to start and sustain derisive laughter and taunts directed towards the sheet-draped culprits. Viewers in sympathy with the ‘culprits’ who failed to heed the ‘clacker’ command were noted for later punishment. The culmination of the day’s torment then became the responsibility of the respective dormitory Nuns. My dormitory Nun, Sister Alexis, was a perfect role model for a female concentration camp guard. She was a gross creature who appeared to enjoy the power she exerted over her young charges. When the day’s parade activities no longer delayed the dormitory finale, the bed-wetter culprits prepared themselves mentally for their approaching evening bedtime ordeal. Sister Alexis must have classified me as an errant ‘bed wetter’ from my bed wetting on my first night in the orphanage. She was no doubt convinced that her duty as a ‘Bride of Christ’ was to emulate Christ’s curing of the lepers by curing her bed wetter charges. Whatever her goal, my tender bottom remained a target for her strap for what seemed an eternity to a small boy. Seen through my eyes when lying face down on my bed, with head on the side restricting my view, Sister Alexis’s ominous path down the bed lines filled me with intense fear. As she waddled into my arc of vision, her human presence was transformed into that of an ogress clad in a white wimple headdress and long white dressing gown that replaced her normal black day attire. From the time she entered the dormitory the air was charged with a scent of fear that would have set a pack of dogs barking in frenzy, Out of habit, or affectation to increase the fear in her charges, Sister Alexis went through a routine of clamping the strap under her armpit while methodically rolling up her sleeves. This served to prolong the agony of her tense victims awaiting punishment. With large forearms displayed and one hand holding the strap, Sister Alexis proceeded down the bed rows to each bed-wetter’s position, whipped up their nightgowns to bare their buttocks and proceeded to deliver the allocated punishment. This varied from one to five strokes depending on the number of times a culprit had wet the bed during that week. I was a five-stroke ace. That is why I never attend church services.

|

Angie Littlefield | 416.282.0646 | angie.littlefield@yahoo.ca |

Demolition photo taken Jr. A. Irving 1960

Demolition photo taken Jr. A. Irving 1960

The ‘bed wetter’ parades were held several times a week during the morning break periods, Sundays and religious holidays exempted. On bed wetter parade days the dormitory Nuns would direct their culprit groups in crocodile formation from their segregated wings to the laundry room in the basement of the administrative section. Once there the novices and veterans were gathered around the soiled sheet hampers and briefed on what they had to do. The new and frightened culprits hung their head in shame and stifled sobs while the old hands looked on in disdain. All were ordered to take a soiled sheet from the hampers and drape this around their head and shoulders. A few of the novices, aware of the embarrassment that lay ahead, tried to adjust the sheets to hide their faces, but the watchful eyes of the escorting Nuns prevented these camouflaging efforts.

The ‘bed wetter’ parades were held several times a week during the morning break periods, Sundays and religious holidays exempted. On bed wetter parade days the dormitory Nuns would direct their culprit groups in crocodile formation from their segregated wings to the laundry room in the basement of the administrative section. Once there the novices and veterans were gathered around the soiled sheet hampers and briefed on what they had to do. The new and frightened culprits hung their head in shame and stifled sobs while the old hands looked on in disdain. All were ordered to take a soiled sheet from the hampers and drape this around their head and shoulders. A few of the novices, aware of the embarrassment that lay ahead, tried to adjust the sheets to hide their faces, but the watchful eyes of the escorting Nuns prevented these camouflaging efforts.